Sleep Apnea Risk Calculator

Opioids can significantly increase your risk of sleep apnea and oxygen drops during sleep. This calculator estimates your risk based on your opioid dosage and other factors. Always consult with your doctor for medical advice.

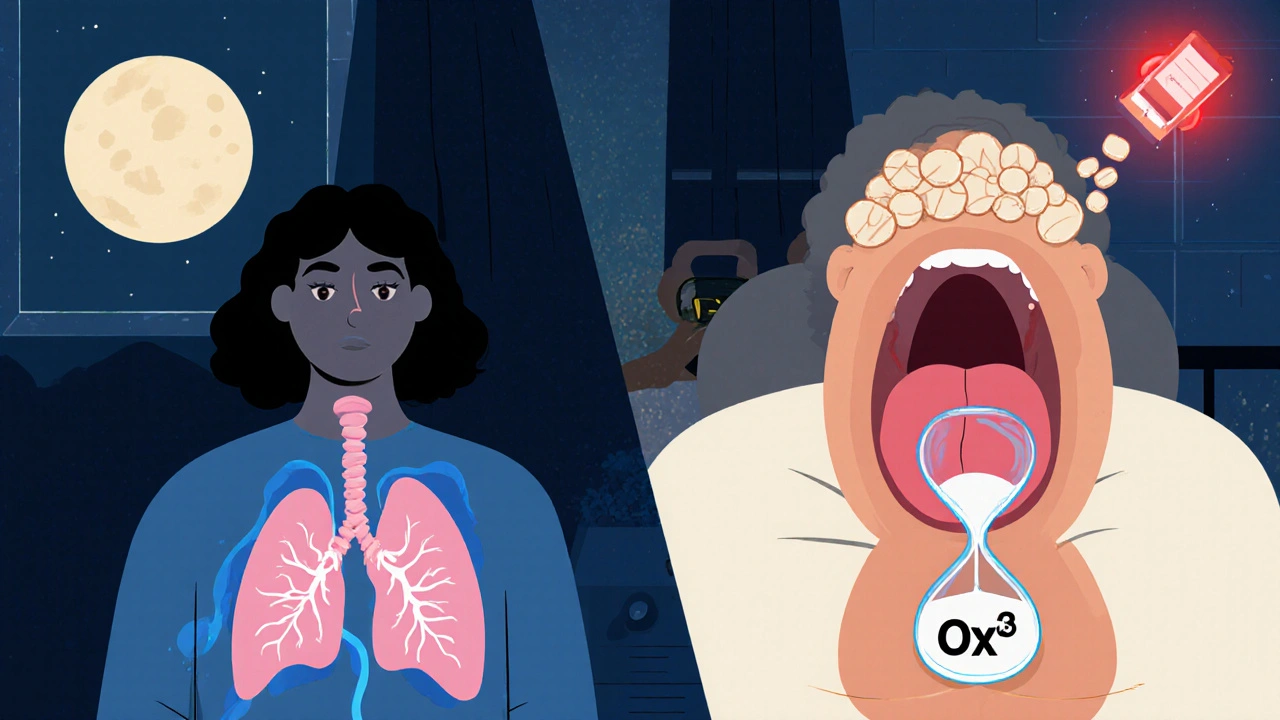

When you take opioids for chronic pain, you’re not just managing discomfort-you might be quietly putting your breathing at risk while you sleep. The danger isn’t just theoretical. For people using opioids long-term, especially at higher doses, the chance of dropping oxygen levels during sleep can jump dramatically. This isn’t about occasional snoring. It’s about nighttime hypoxia-a dangerous dip in blood oxygen that can lead to heart strain, brain damage, or even sudden death. And it’s happening far more often than most doctors or patients realize.

How Opioids Quiet Your Breathing at Night

Opioids don’t just block pain signals. They also slow down the brain’s natural drive to breathe. This effect is strongest during sleep, when your body isn’t actively fighting to stay awake. The brainstem regions that control breathing-like the pre-Bötzinger complex-get suppressed by opioids, making you less responsive to low oxygen and high carbon dioxide levels. Studies show this reduces your body’s ability to react to low oxygen by 25-50%, and its response to rising CO2 by 30-60%. That means when your airway closes during sleep, your brain doesn’t wake you up fast enough-or sometimes at all-to take a breath.At the same time, opioids relax the muscles in your throat. The genioglossus, the main muscle holding your airway open, becomes sluggish. This makes it easier for your tongue and soft tissues to collapse backward during sleep, blocking airflow. The result? A double hit: your brain isn’t telling you to breathe, and your airway is physically closing.

Central Apnea Isn’t Just for Heart Patients

Most people think sleep apnea means loud snoring and daytime tiredness-that’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). But opioids trigger something different: central sleep apnea (CSA). In CSA, your brain literally forgets to signal your lungs to breathe. You don’t snore. You don’t gasp. You just stop breathing for 10-30 seconds, repeatedly, through the night. Polysomnography studies show chronic opioid users have central apnea indices (CAI) of 10-15 events per hour, compared to 2-5 in non-users. For those on high-dose methadone (over 100 mg/day), more than 65% have CAI above 20.And it gets worse. Many people have both OSA and CSA at the same time. The opioid weakens the airway and the brain’s drive to breathe, turning mild snoring into life-threatening pauses. One study found that 71% of people on long-term opioids had moderate-to-severe sleep apnea (AHI ≥15). Nearly half had severe apnea (AHI ≥30). That’s not rare. That’s the norm.

Who’s at the Highest Risk?

Not everyone on opioids develops this. But certain factors make it much more likely:- Dose matters: Every additional 10 mg of morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD) increases your AHI by 5.3%. Doses over 50 MEDD are a red flag.

- Type of opioid: Methadone carries the highest risk-4.2 times more likely to cause severe apnea than other opioids.

- Pre-existing OSA: If you already have sleep apnea, opioids triple your risk of oxygen levels dropping below 80% during sleep.

- Obesity: A BMI over 30 increases vulnerability, especially when combined with opioid use.

- Age: Older adults have weaker respiratory control and are more sensitive to opioid effects.

One study found that 80% of chronic opioid users had central sleep apnea (CAI ≥5). Another showed 68% spent more than five minutes per night with oxygen saturation below 88%. For reference, healthy adults rarely dip below 90% during sleep. These aren’t minor dips-they’re medical emergencies waiting to happen.

Why Doctors Miss It

Most patients don’t report nighttime breathing problems. They don’t wake up gasping. They just feel exhausted all day. Doctors, focused on pain control, rarely ask about sleep. A 2021 survey of 350 primary care doctors showed only 28% routinely screen for sleep apnea before prescribing opioids. Many say they don’t have access to sleep specialists. Others think it’s not their job.But the data doesn’t lie. At the University of Michigan, 78% of opioid-treated pain patients referred for sleep studies had undiagnosed apnea. At the Cleveland Clinic, implementing routine screening cut opioid-related respiratory events by 41% in 18 months. This isn’t just about comfort-it’s about survival.

What Can Be Done?

The good news: this risk can be managed. The first step is screening. If you’re on opioids at doses over 50 MEDD-or have risk factors like obesity, snoring, or daytime fatigue-get a sleep study. Polysomnography is still the gold standard, but newer home tests like the Nox T3 Pro (FDA-cleared in January 2023) are now validated specifically for opioid users, with 92% accuracy in detecting moderate-to-severe apnea.For obstructive sleep apnea, CPAP is the first-line treatment. But adherence is low-only 58% of opioid users stick with it, compared to 72% of others. Why? Opioids cause brain fog, dry mouth, and discomfort that make wearing the mask harder. Some patients need help adjusting, or a different mask type.

For central apnea, CPAP can still help, but sometimes it’s not enough. A promising new option is acetazolamide, a diuretic that stimulates breathing. A clinical trial at UCSD found it reduced apnea events by 35% in opioid users compared to placebo. It’s not FDA-approved for this use yet, but doctors are prescribing it off-label with good results.

Other strategies:

- Lower the dose: If pain is controlled, reducing opioid use can reverse some breathing issues.

- Switch opioids: Some, like buprenorphine, have less respiratory depression. Talk to your pain specialist.

- Positional therapy: Sleeping on your side can reduce airway collapse.

- Avoid alcohol and sedatives: These make everything worse.

Real Stories, Real Consequences

On Reddit’s r/ChronicPain forum, users describe waking up choking, feeling like they’re drowning in air. One wrote: “I started oxycodone and suddenly couldn’t sleep without gasping. My wife said I stopped breathing for 10 seconds at a time. I thought I was going crazy-until the sleep study confirmed it.” After starting CPAP, he said: “I haven’t felt this awake in years.”But not everyone gets better. One case report described a patient who stopped opioids entirely but still had severe central apnea. His brain had adapted to the drug’s suppression-and didn’t recover. That’s why early detection matters. Waiting too long might make the damage permanent.

What You Should Do Now

If you’re on opioids for chronic pain:- Ask yourself: Do I feel tired all day? Do I snore? Have I been told I stop breathing while sleeping?

- If yes to any, ask your doctor for a sleep apnea screening-especially if you’re on 50 MEDD or more.

- If you have sleep apnea, don’t delay treatment. CPAP or acetazolamide can save your life.

- Don’t assume your pain doctor knows this risk. Bring the CDC’s 2022 opioid guidelines to your appointment.

This isn’t about stopping pain treatment. It’s about making it safer. Millions of people rely on opioids. But no one should have to risk their life to sleep. Screening is simple. Treatment works. Ignoring it? That’s the real danger.

Can opioids cause sleep apnea even if I’ve never snored before?

Yes. Opioids can trigger central sleep apnea, which doesn’t involve snoring. This happens when the brain stops sending signals to breathe during sleep. Many people with opioid-induced apnea have no history of snoring or daytime sleepiness. That’s why screening with a sleep study is critical-even if you feel fine.

Is it safe to take opioids if I already have sleep apnea?

It’s possible, but risky. People with untreated sleep apnea who start opioids have a 3.7-fold higher risk of severe nighttime oxygen drops. If you have sleep apnea and need opioids, CPAP therapy must be started and optimized first. Never begin or increase opioids without treating your apnea first.

What’s the safest opioid for someone with sleep apnea?

Buprenorphine appears to have less respiratory depression than methadone or oxycodone. Studies show it’s less likely to cause central apnea. But no opioid is completely safe for people with sleep apnea. The goal should be using the lowest effective dose for the shortest time, with sleep monitoring.

Can I use a home sleep test if I’m on opioids?

Yes-but only if the device is validated for opioid users. The Nox T3 Pro received FDA clearance in January 2023 specifically for this group, with 92% accuracy in detecting moderate-to-severe apnea. Standard home tests may miss central apnea patterns caused by opioids. Always ask your doctor which device they recommend.

Will stopping opioids fix my sleep apnea?

Sometimes. Many people see improvement in central apnea after reducing or stopping opioids. But in some cases, especially with long-term, high-dose use, the brain’s breathing control doesn’t fully recover. That’s why early intervention matters. Waiting too long could lead to permanent changes in respiratory control.

Ted Carr

This is the kind of post that makes me wonder if the medical industry is just selling us slow-motion suicide with a side of oxycodone and a smile.

They give us pills to numb the pain, then act shocked when we stop breathing. Who knew the cure was worse than the disease?

Jonathan Debo

It is, indeed, a profoundly concerning phenomenon-particularly when one considers the neurophysiological underpinnings of opioid-induced central sleep apnea (CSA), which directly impairs the brainstem’s chemoreceptor sensitivity to hypercapnia and hypoxia.

Moreover, the suppression of the pre-Bötzinger complex-responsible for respiratory rhythm generation-is both dose-dependent and temporally cumulative, as evidenced by multiple peer-reviewed polysomnographic studies (e.g., JAMA Neurology, 2020; Sleep Medicine Reviews, 2021).

It is not merely anecdotal; it is mechanistic, reproducible, and, tragically, under-recognized by primary care practitioners who lack formal training in sleep medicine.

Abigail Jubb

I’ve been on 80mg of methadone for five years.

I thought my exhaustion was just from ‘living with pain.’

Then my husband started recording me at night.

He said I’d stop breathing for 20 seconds… then gasp like I’d just been dragged out of a well.

I cried for three days after the sleep study.

I didn’t know I was dying in my sleep.

And no one told me.

Not my doctor.

Not the pharmacist.

Not even the ‘pain management specialist’ who gave me the script.

I’m on CPAP now.

I feel like a human again.

But I’ll never forgive them for not warning me.

Hope NewYork

So let me get this straight-doctors are giving people drugs that make them stop breathing… and then they want you to pay for a $2000 machine to fix it?

And if you can’t afford it, you just… die in your sleep?

That’s not healthcare. That’s a death sentence with a co-pay.

And don’t even get me started on how they act like it’s your fault for not ‘asking’.

Like you’re supposed to know all the side effects of every pill they hand you.

Yeah right.

They don’t even read the damn labels.

Bonnie Sanders Bartlett

If you’re on opioids, please, please, please get checked for sleep apnea.

I know it sounds scary. I was scared too.

But the machine? It’s not as bad as you think.

My husband helped me adjust the mask. We watched videos together.

After two weeks, I stopped waking up with headaches.

I actually started enjoying mornings again.

You deserve to sleep without fear.

You’re not weak for needing help.

You’re brave for asking.

Melissa Delong

Have you considered that this might all be a pharmaceutical industry scam to sell CPAP machines?

What if the real danger isn’t opioids-but the sleep study industry?

They profit from fear.

They profit from labels.

They profit from making people feel broken so they’ll buy devices.

And who benefits?

Not you.

Not your health.

Just the corporations.

Ask yourself: Who wrote these guidelines?

Marshall Washick

I’ve been on long-term opioids since my accident in 2015.

I never snored. Never felt tired during the day.

Then one night, my wife shook me awake because I turned blue.

She called 911.

I didn’t even know I’d stopped breathing.

They told me I had a CAI of 22.

They put me on CPAP.

It felt like a prison at first.

But now? I sleep like a baby.

I don’t know why no one told me this could happen.

I just wish I’d known sooner.

Abha Nakra

As someone who works in pain management in India, I see this every day.

Patients come in with severe pain, and we give them opioids because we have no other options.

But we don’t have sleep labs.

We don’t have home tests.

We don’t even have enough doctors who know this risk.

So we do the best we can.

But this post? It’s a wake-up call.

Not just for the West.

For everywhere.

We need global awareness.

Not just in the US.

Everywhere.

Neal Burton

Let’s be honest-this isn’t about opioids.

This is about how society has turned suffering into a product.

We don’t treat pain anymore-we commodify it.

We don’t heal-we mask.

We don’t listen-we prescribe.

And when the body rebels? We slap on a machine.

And call it progress.

But the truth? We’ve lost touch with what healing even means.

And now people are dying because we’re too busy selling solutions to ask what’s really broken.

Tamara Kayali Browne

It is statistically irresponsible to assert that ‘nearly half had severe apnea’ without disclosing the confidence intervals or adjusting for BMI, age, and comorbidities.

Furthermore, the cited study from the University of Michigan utilized a referral bias population, which inherently overestimates prevalence.

Additionally, the Nox T3 Pro’s 92% accuracy claim is based on a sample size of n=47, with no external validation.

Until peer-reviewed, large-scale, prospective cohort data is published, these claims remain speculative at best-and alarmist at worst.

Lori Johnson

My mom’s on methadone.

She’s 72.

She never snored before.

Now she wakes up coughing every night.

I begged her doctor for a sleep study.

He said, ‘She’s fine, she’s not gasping.’

So I bought a home monitor.

It showed 18 apneas per hour.

She’s on CPAP now.

She says she feels 20 years younger.

But I’m still mad.

Why did I have to do all the work?

He’s supposed to be the doctor.

Tatiana Mathis

There’s something deeply human about this whole issue.

It’s not just about biology or dosage or brainstem suppression.

It’s about how we treat people who are in pain.

We hand them pills like they’re candy.

We don’t ask how they sleep.

We don’t check their oxygen.

We don’t sit with them while they cry about how tired they are.

We just write another script.

And then we wonder why they feel alone.

Maybe the real treatment isn’t CPAP.

Maybe it’s being seen.

Really seen.

Before the breathing stops.

Before it’s too late.