Imagine trying to hear your partner speak in a quiet room, but their voice sounds muffled-like they’re talking through a pillow. You keep asking them to repeat themselves, but you’re not sure if it’s them or you. Then you realize you’re struggling to hear the low hum of a refrigerator, or the bass in music. If this sounds familiar, and you’re in your 30s or 40s, it might not be aging-it could be otosclerosis.

What Exactly Is Otosclerosis?

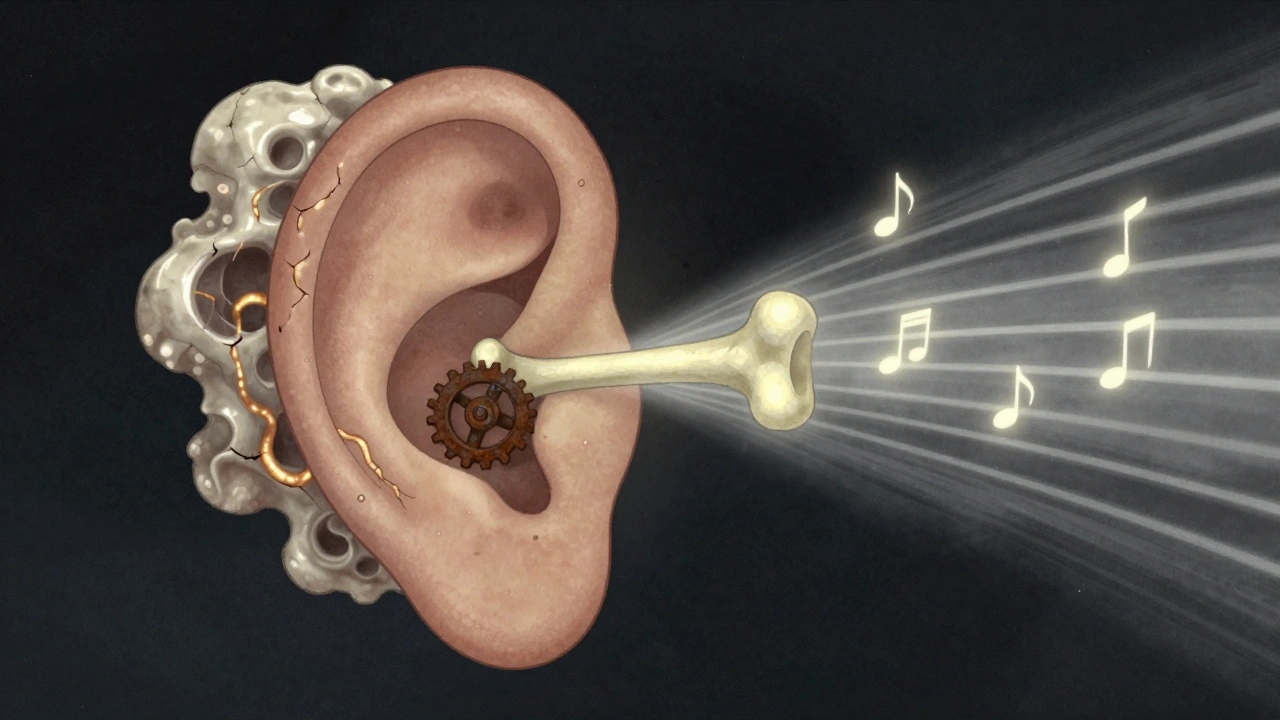

Otosclerosis is a condition where abnormal bone grows inside your middle ear, locking up one of the smallest bones in your body: the stapes. This bone, about the size of a grain of rice, normally vibrates like a tiny piston to send sound from your eardrum to the inner ear. When it gets stuck, sound can’t travel properly. That’s why you lose hearing-not because your ears are damaged, but because the mechanism that carries sound is frozen in place.

This isn’t just random bone growth. It’s a slow, steady process where normal bone is replaced by spongy, porous bone that eventually hardens. The spot where this happens is usually right at the oval window-the door between the middle ear and the inner ear. CT scans can show these tiny, dark spots where the bone has changed, often measuring less than 2 millimeters. It’s not cancer. It’s not an infection. It’s a glitch in how your body rebuilds bone in one very specific spot.

Who Gets Otosclerosis-and Why?

Otosclerosis doesn’t hit everyone evenly. It’s most common in women, especially between ages 30 and 45. About 70% of cases occur in women, and if your mom or sister has it, your risk jumps significantly. Around 60% of people with otosclerosis have a family member with it too. Research has found at least 15 genes linked to the condition, with the RELN gene on chromosome 7 being the most strongly tied.

It’s also more common in people of European descent. Rates are about twice as high in Caucasian populations compared to African or Asian groups. In the UK, roughly 1 in 200 people have it. In the U.S., that translates to about 3 million people. And while it’s not rare, many people go years without a diagnosis because the symptoms creep in slowly.

How Do You Know If You Have It?

The biggest clue? Progressive hearing loss that starts in one ear, then often spreads to the other. Unlike age-related hearing loss, which makes high-pitched sounds like birds chirping or children’s voices harder to hear, otosclerosis usually hits low-pitched sounds first. You might notice:

- Struggling to hear whispers or soft speech

- People saying you’re mumbling-even when you know you’re speaking clearly

- Difficulty hearing in noisy rooms, even though your hearing seems fine in quiet ones

- Feeling like your own voice sounds louder or echoey

Many people also get tinnitus-a ringing, buzzing, or hissing in the ears. In fact, 80% of people with otosclerosis report bothersome tinnitus, and about one-third say it keeps them up at night.

The only way to confirm it? An audiogram. This hearing test shows a clear gap between air conduction (sound coming through the ear canal) and bone conduction (sound sent directly through the skull). In otosclerosis, that gap is usually between 20 and 40 decibels. Speech tests often come back normal, which helps doctors rule out other issues like nerve damage.

What’s the Difference Between Otosclerosis and Other Hearing Losses?

It’s easy to confuse otosclerosis with other types of hearing loss. Here’s how it stacks up:

- Noise-induced hearing loss: Starts with high frequencies. You miss birdsong, alarms, or beeps. Otosclerosis hits low tones first.

- Presbycusis (age-related): Usually begins after 65 and affects high pitches. Otosclerosis strikes younger adults, often in their 30s.

- Meniere’s disease: Comes with dizziness, ear pressure, and fluctuating hearing. Otosclerosis doesn’t cause vertigo-it’s a steady decline.

- Eustachian tube dysfunction: Feels like clogged ears, often after a cold. Otosclerosis doesn’t improve with decongestants.

That’s why misdiagnosis is common. One study found 22% of otosclerosis patients waited an average of 18 months before getting the right diagnosis. They were told they had earwax, allergies, or stress-when the real problem was a bone that wouldn’t move.

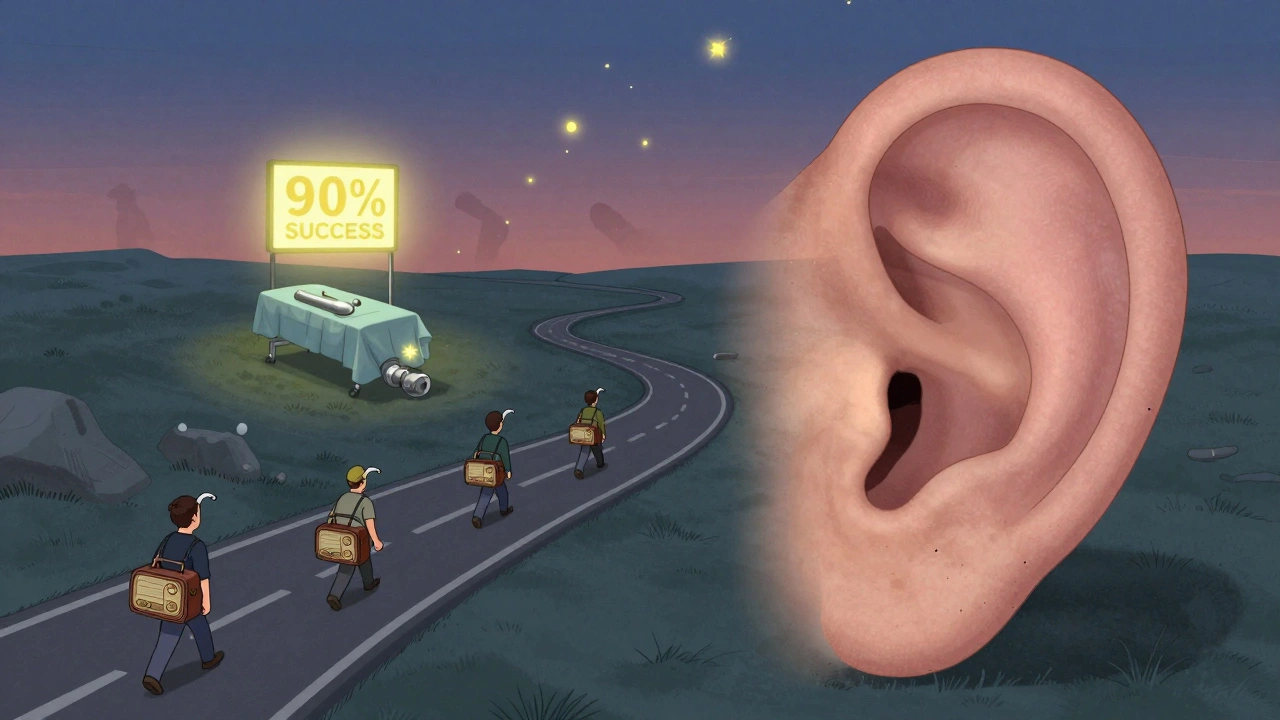

Treatment Options: Surgery vs. Hearing Aids

Here’s the good news: otosclerosis is one of the most treatable forms of hearing loss. You have two solid options, and both work well.

1. Hearing Aids

If your hearing loss is mild or you’re not ready for surgery, hearing aids can help a lot. They amplify sound, especially in the low frequencies where otosclerosis hits hardest. About 65% of people start here. Modern devices can be programmed to boost only the frequencies you’re missing, making conversations clearer without turning everything else up too loud.

But hearing aids don’t fix the problem-they just compensate for it. The bone is still stuck. And over time, the hearing loss can get worse, meaning you’ll need stronger amplification.

2. Stapedectomy or Stapedotomy

This is where surgery comes in. A stapedectomy removes part of the fixed stapes and replaces it with a tiny prosthesis-usually made of titanium or platinum. A newer version, called a stapedotomy, drills a small hole in the stapes footplate and inserts a piston-like device. It’s a delicate operation, done under a microscope, and takes about an hour.

Success rates? Around 90-95% of patients see major improvement. The air-bone gap closes to within 10 decibels in most cases. One teacher in Florida said after her surgery, she could finally hear students whispering in the back row. That’s the kind of life change this can bring.

There’s a catch: surgery isn’t risk-free. About 1% of patients end up with worse hearing-sometimes permanently. That’s why your surgeon must explain this risk clearly before you sign off. Also, if you’ve had a previous ear surgery, the success rate drops to 75%. That’s why choosing an experienced otologist matters.

And here’s something new: in March 2024, the FDA approved a new prosthesis called StapesSound™, coated with titanium-nitride to reduce scarring. Early results show a 94% success rate at one year-better than older models.

Can You Slow It Down Without Surgery?

Yes. While surgery fixes the problem, it doesn’t stop the disease from spreading. In about 10-15% of cases, otosclerosis reaches the inner ear and causes sensorineural hearing loss-which surgery can’t fix.

That’s where sodium fluoride comes in. A 2024 study showed patients taking a low-dose fluoride supplement slowed their hearing loss by 37% over two years compared to those who didn’t. It doesn’t reverse damage, but it can keep things from getting worse. It’s not a cure, but it’s a tool for people who aren’t ready for surgery-or who have early signs but aren’t yet at the point where hearing aids aren’t enough.

Some doctors also recommend avoiding loud noise and quitting smoking, since both can stress the inner ear. There’s no proof that diet or supplements help, but staying healthy won’t hurt.

What Happens If You Do Nothing?

Left untreated, otosclerosis doesn’t cause total deafness-but it does get worse. On average, hearing drops 15 to 20 decibels over five years. That might not sound like much, but it’s the difference between understanding a conversation in a quiet room and needing to read lips. For many, it means avoiding social events, feeling isolated, or being mistaken for not listening when they’re just not hearing.

And if the condition spreads to the cochlea, you might lose the ability to hear high frequencies too-making speech sound unclear even with amplification. That’s why early diagnosis matters.

Where Do You Go From Here?

If you suspect you have otosclerosis, start with your GP. They can refer you to an audiologist for a hearing test. If the results show a conductive hearing loss with an air-bone gap, you’ll be sent to an otolaryngologist (ear, nose, and throat specialist) who does ear surgery.

Ask them:

- Do I have a clear air-bone gap on my audiogram?

- Could this be otosclerosis, or could it be something else?

- What’s my current hearing loss level?

- Do you recommend hearing aids, medication, or surgery?

- How many stapedotomies do you perform each year?

Don’t rush into surgery. Get a second opinion if you’re unsure. But don’t wait too long either. The earlier you act, the better the outcome.

Support and Resources

You’re not alone. The Hearing Loss Association of America has over 1,200 active members in their otosclerosis support group. Online forums like Reddit’s r/HearingLoss are full of people sharing stories like: “I thought my husband was being rude-he just couldn’t speak loudly enough for me to hear.”

There are also patient guides from the American Academy of Otolaryngology and the American Hearing Research Foundation. They offer clear, practical advice on what to expect before and after surgery, how to talk to your employer about accommodations, and how to choose the right hearing aid.

And if you’re a woman in your 30s or 40s with unexplained hearing loss-especially if your mom or sister has it-don’t ignore it. Get tested. You might just find out that the problem isn’t your ears. It’s a tiny bone that’s been holding on too tight.

Is otosclerosis hereditary?

Yes, otosclerosis often runs in families. About 60% of people with the condition have at least one close relative who also has it. Research has identified 15 genes linked to otosclerosis, with the RELN gene being the most strongly associated. If a parent has it, your risk is higher-especially if you’re female.

Can otosclerosis cause complete deafness?

No, otosclerosis rarely leads to total deafness. It typically causes conductive hearing loss, which means sound can’t reach the inner ear properly-but the inner ear itself is still working. In about 10-15% of cases, it spreads to the cochlea and causes sensorineural hearing loss, which is harder to treat. But even then, most people retain some useful hearing, especially with hearing aids or surgery.

Is stapedectomy safe?

Stapedectomy and stapedotomy are very safe when done by an experienced surgeon. Success rates are 90-95%, with most patients regaining near-normal hearing. But there’s a small risk-about 1%-of permanent hearing loss or dizziness after surgery. That’s why it’s critical to choose a surgeon who performs these procedures regularly and to fully understand the risks before agreeing to surgery.

Do hearing aids work for otosclerosis?

Yes, hearing aids work very well for otosclerosis, especially in the early stages. They’re programmed to amplify low-frequency sounds, which are the first to be affected. Many people use them for years before deciding on surgery. They don’t fix the bone problem, but they restore hearing function and improve quality of life.

Can sodium fluoride cure otosclerosis?

No, sodium fluoride doesn’t cure otosclerosis. But studies show it can slow the progression of hearing loss by about 37% over two years. It’s often recommended for people with early-stage disease who aren’t ready for surgery, or those whose condition is spreading to the inner ear. It’s taken as a daily pill under medical supervision.

Why is otosclerosis more common in women?

The exact reason isn’t fully understood, but hormones appear to play a role. Many women first notice symptoms during pregnancy, when hearing loss can suddenly worsen. Estrogen may influence bone remodeling in the ear, making women more susceptible. This is why 70% of diagnosed cases are in women, especially between ages 30 and 45.

James Kerr

My grandma had this and didn’t even know it for years. Thought she was just being stubborn. Got her hearing aids and now she’s yelling at the TV again-just like before. 😄

Rashi Taliyan

Oh my god, I thought I was going crazy! I kept thinking my husband was mumbling, but it was me… I couldn’t hear him unless he shouted. I cried when the audiogram showed the gap. This article? It felt like someone read my diary.

Rashmin Patel

Y’all need to stop ignoring this. I’m Indian, and my mom had otosclerosis-no one in our family even knew it could be genetic. We thought it was just ‘old age’ or ‘stress.’ I got tested at 32 because my mom’s hearing dropped fast after pregnancy. Turns out, I had early signs. Sodium fluoride helped slow it down. Don’t wait till you’re missing your kid’s voice. You’ll regret it. 💪

Gavin Boyne

So let me get this straight-we’ve got a condition where your ear bone turns into a stubborn toddler refusing to move, and the solution is either a tiny titanium piston or a fluoride pill? And the FDA just approved a new one called StapesSound™? Sounds like a sci-fi movie where the villain is your own skeleton. Meanwhile, I’m over here Googling ‘why does my dog hear the fridge before I do?’

Kara Bysterbusch

As someone who has spent years advocating for auditory health equity, I find this article profoundly illuminating. The demographic disparities-particularly the elevated prevalence among women of European descent-are not merely clinical observations; they are sociocultural markers that demand systemic attention. The absence of robust public screening programs in primary care settings represents a critical gap in preventive medicine. Furthermore, the efficacy of sodium fluoride as a disease-modifying agent, while statistically significant, remains underutilized due to physician unfamiliarity and patient hesitancy. We must bridge this knowledge chasm.

sagar bhute

Everyone’s acting like this is some rare miracle cure. Newsflash: surgery has a 1% chance of making you deaf. That’s not a risk-it’s a gamble. And fluoride? That’s just putting a bandaid on a broken leg. You people are too scared to face reality. You’d rather take a pill than deal with the fact that your body is failing. Pathetic.

Cindy Lopez

There’s a missing comma after ‘low-pitched sounds first’ in the third paragraph. Also, ‘stapedotomy’ is misspelled once as ‘stapedotomy’-wait, no, that’s correct. Never mind. But the capitalization of ‘FDA’ is inconsistent in the third paragraph. And ‘1 in 200’ should be ‘one in two hundred’ in formal writing. This article is otherwise excellent.

Jim Schultz

Wow. Just… wow. You actually mentioned RELN gene and titanium-nitride coating? You must’ve copied this from a textbook. I’ve been reading peer-reviewed journals since 2010, and this is… almost credible. But you missed the 2023 meta-analysis on estrogen receptor polymorphisms in otosclerosis. Shame. Also, your ‘1 in 200’ statistic? That’s outdated. It’s 1 in 170 in urban US populations now. You really should’ve checked your sources.

Kidar Saleh

I’ve worked with deaf communities in London for over a decade. The silence that comes with untreated otosclerosis isn’t just physical-it’s emotional. People withdraw. They stop laughing. They stop joining dinners. It’s not about volume. It’s about connection. This article doesn’t just explain a condition-it explains loneliness. Thank you.

Chloe Madison

YOU ARE NOT ALONE. Seriously. I was diagnosed at 34. Thought I was losing my mind. I cried in the audiologist’s office. But guess what? I had surgery last month. Now I hear my cat purr. I hear my coffee machine gurgle. I hear my best friend say ‘I love you’ without her having to yell. You can do this. You’re stronger than you think. 🌟

Vincent Soldja

Interesting. The data is sound. The tone is appropriate. The structure is logical. I recommend further peer review before wider dissemination.

Makenzie Keely

Thank you for writing this with such clarity and compassion! I’m a speech-language pathologist, and I’ve seen too many patients suffer for years because doctors dismissed their hearing loss as ‘just stress’ or ‘earwax.’ The fact that you included the air-bone gap details and the new StapesSound™ prosthesis? That’s gold. I’m sharing this with every patient I see. Also-YES to sodium fluoride for early cases! I’ve had three patients stabilize their hearing with it. It’s not magic, but it’s hope-and hope matters.