When a brand-name drug loses its patent, a flood of cheaper generic versions hits the market. The savings aren’t theoretical-they’re real, measurable, and in the billions. Every year, the FDA approves hundreds of generic drugs, and each approval triggers a sharp drop in price, often by more than 70%. These price drops translate directly into billions saved by patients, insurers, and government programs. But the numbers change every year. Some years, savings spike. Others, they dip. Why? And what does the year-by-year breakdown actually tell us about the real impact of generics?

How the FDA Measures Savings from New Generic Approvals

The FDA doesn’t just count how many generic drugs get approved. It tracks the actual money saved in the first year after each approval. This is called the first-year savings metric. It looks at one thing: what happened to the price and volume of a drug after a generic version entered the market.

For example, if a brand-name drug cost $100 per pill and a generic version came in at $20, and 1 million prescriptions were filled, the immediate savings would be $80 million. But it’s not that simple. Often, the brand-name company lowers its own price to compete, even before the generic takes over. The FDA accounts for that too. Their formula: (Brand price - Generic price) × Generic volume + (Brand price reduction × Brand volume).

This method only counts savings from drugs approved that year. It ignores generics that were already on the market. That’s why the numbers look small compared to other reports. In 2022, the FDA reported $5.2 billion in savings from new generic approvals. That doesn’t mean $5.2 billion was saved total-it means $5.2 billion came from drugs approved that year, during their first 12 months on the market.

The Year-by-Year Breakdown: Peaks and Lulls

The savings from new generic approvals don’t move in a straight line. They jump around based on which drugs lose patent protection. Some years, a few blockbuster drugs go generic. Other years, it’s mostly smaller, lower-cost drugs.

- 2018: $2.7 billion in savings from new generic approvals

- 2019: $7.1 billion-the highest year in the past decade. Why? Because major drugs like adalimumab (Humira) and esomeprazole (Nexium) lost patent protection. These were multi-billion-dollar drugs. Their generics cut prices by over 80%.

- 2020: $1.1 billion. A sharp drop. No major blockbusters went generic that year. The pandemic also disrupted supply chains and slowed approvals.

- 2021: $1.37 billion. Still low, but a few high-value drugs came through, including generics for trastuzumab (Herceptin), a cancer drug. Five drugs accounted for half of all savings that year.

- 2022: $5.2 billion. A big rebound. The FDA noted that several approvals were for drugs in "relatively large markets." This included generics for abiraterone acetate (Zytiga), used for prostate cancer, and ranibizumab (Lucentis), used for eye disease. Both had annual sales over $2 billion before generics.

The pattern is clear: savings depend on what’s expiring. One big drug can outpace dozens of small ones. That’s why 2019 and 2022 were so high-they hit the jackpot. 2020 and 2021 were flat because the pipeline was thin.

Total Savings: What the Industry Reports

The FDA’s number only tells part of the story. The Association for Accessible Medicines (AAM) looks at the entire market. They calculate how much money was saved in a calendar year from all generic drugs in use-not just the ones approved that year.

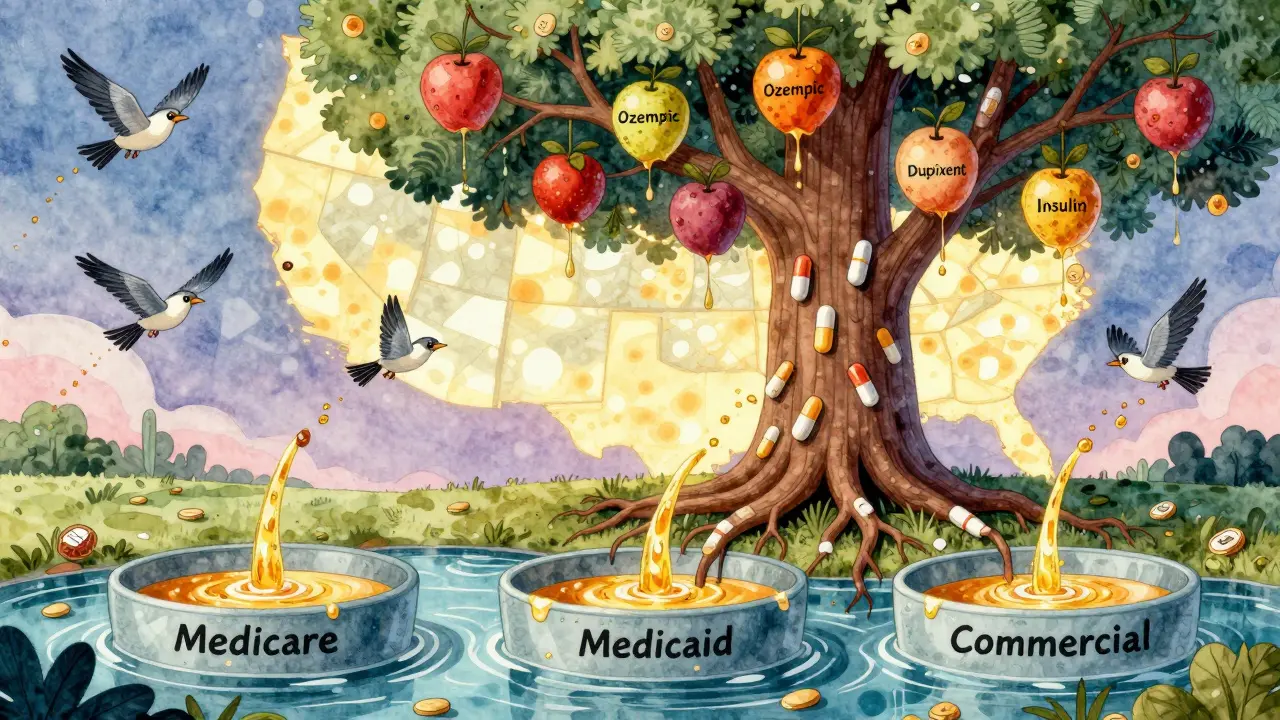

In 2023, AAM reported $445 billion in total savings from generics and biosimilars. That’s not just one year’s worth of new approvals-it’s the cumulative savings from every generic drug sold that year. Here’s how it breaks down:

- Medicare: $137 billion saved

- Commercial insurers: $206 billion saved

- Medicaid: $102 billion saved

Therapeutic areas show where the biggest savings happened:

- Heart disease: $118.1 billion

- Mental health: $76.4 billion

- Cancer: $25.5 billion

These numbers dwarf the FDA’s annual approval figures. Why? Because generics are used in 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S., but only cost 13% of total drug spending. That’s the power of scale. Even small savings on millions of pills add up fast.

Why the Two Numbers Are Both Right

It’s easy to get confused. One report says $5.2 billion. Another says $445 billion. Which one’s correct? Both. They’re measuring different things.

The FDA’s number is like tracking new cars sold in a month. It shows how many new models hit the road and how much they changed the market right away. The AAM number is like tracking how much money drivers saved on gas and repairs over the entire year because they drive mostly used cars. One measures new entries. The other measures total impact.

Think of it this way: A new generic for a heart drug approved in 2021 might save $500 million in its first year. But in 2023, that same generic is still being used-millions of times. The AAM counts that $500 million again, plus all the other generics in use. The FDA doesn’t. That’s why AAM’s number keeps growing every year, while the FDA’s number jumps up and down.

Who Benefits the Most?

Patients don’t always see the full savings. Even though generics cost 80-90% less than brand names, many patients still pay high copays. Why? Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) often keep a big chunk of the savings.

A 2023 Senate Finance Committee report found that only 50-70% of the price drop from generics actually reaches the patient. The rest gets absorbed by PBMs, insurers, or manufacturers through rebates and contracts. That’s why a drug that dropped from $1,000 to $100 might still cost a patient $50 out of pocket.

But for many, even that’s a win. The average generic copay is $6.97. For chronic conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes, that means patients pay less than $1 a day. Pharmacists report 92% of generic prescriptions are filled for under $20. That’s life-changing for people on fixed incomes.

State Medicaid programs saw massive savings. California’s Medi-Cal saved $23.4 billion in a single year. Alaska, with a much smaller population, still saved $354 million. The scale of savings scales with population-and the number of generics used.

What’s Next for Generic Savings?

The pipeline is strong. Dozens of blockbuster drugs are set to lose patent protection over the next five years, including semaglutide (Ozempic), dupilumab (Dupixent), and insulin glargine. When generics hit, savings could jump again.

The FDA is also working to speed up approvals for complex generics-drugs that are harder to copy, like inhalers or injectables. In 2022, they approved 742 generic applications, up from 633 in 2021. Their goal: get 95% of standard applications reviewed in under 10 months. Faster approvals mean faster savings.

Biosimilars-generic versions of biologic drugs-are starting to make a dent. As of August 2024, the FDA had approved 59 biosimilars. They’re not yet saving as much as traditional generics, but their prices are falling. In 2024, biosimilar savings are expected to hit $10 billion, and that number will climb.

Still, challenges remain. Some brand companies use legal tricks, like patent thickets or REMS restrictions, to delay generic entry. The FDA’s 2023 Drug Competition Action Plan is targeting these barriers. If they succeed, the next wave of savings could be even bigger.

The Bigger Picture

Generic drugs are one of the most effective cost-control tools in American health care. They don’t require new technology or complex reforms. They just need time, competition, and regulatory support.

Since 2014, generics and biosimilars have saved the U.S. health system over $3.1 trillion. That’s more than the entire GDP of Canada. In 2023 alone, those savings covered the cost of health care for 100 million Americans for a full year.

The year-by-year numbers fluctuate, but the trend is undeniable: every new generic approval is a direct hit to drug prices. The savings aren’t always immediate for patients, but they’re real, measurable, and growing. And as more expensive drugs go generic, the impact will only get larger.

How much money do generic drugs save Americans each year?

In 2023, generic drugs and biosimilars saved the U.S. health care system $445 billion, according to the Association for Accessible Medicines. This includes savings across Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers. The FDA reports additional savings from new generic approvals-$5.2 billion in 2022 alone-but this only reflects the first-year impact of drugs approved that year, not the total market savings.

Why do generic drug savings vary so much from year to year?

Savings spike when high-revenue brand-name drugs lose patent protection. For example, in 2019, the generic versions of Humira and Nexium led to $7.1 billion in savings from new approvals. In 2020, no major drugs went generic, so savings dropped to $1.1 billion. The timing of patent expirations creates a "lottery effect"-some years are big, others are small.

Do patients actually pay less when generics are approved?

Sometimes, but not always. While generics cost 80-90% less than brand drugs, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) often keep part of the savings through rebates. A 2023 Senate investigation found only 50-70% of the price drop reaches patients. Still, the average generic copay is just $6.97, and 92% of generics are filled for under $20-making them far more affordable than brand names.

What’s the difference between FDA and AAM savings reports?

The FDA measures savings from drugs approved in a single year during their first 12 months on the market. The AAM measures total savings from all generic drugs used in a calendar year, regardless of when they were approved. The FDA number shows immediate impact; the AAM number shows total market effect. Both are valid-they just measure different things.

Are biosimilars saving as much as traditional generics?

Not yet. As of August 2024, the FDA has approved 59 biosimilars, but they’re still a small part of the market. Biosimilars are more complex and expensive to produce than traditional generics, so their price discounts are smaller. In 2024, biosimilar savings are estimated at $10 billion, compared to $445 billion from traditional generics. But their savings are growing quickly as more biologics lose patent protection.

What’s the future of generic drug savings?

The future looks strong. Dozens of high-cost drugs-including Ozempic, Dupixent, and insulin glargine-are set to lose patent protection over the next five years. The FDA is also accelerating reviews for complex generics and targeting legal delays by brand manufacturers. The Association for Accessible Medicines projects cumulative savings will reach $3.9 trillion by 2028, with annual savings potentially hitting $500 billion by the end of the decade.

Kathryn Weymouth

The FDA’s first-year savings metric is so clever-it isolates the immediate market shock of each new generic, like a controlled experiment in real time. But I’ve always wondered: how do they account for regional price variations? A drug might drop 80% nationally, but in rural pharmacies, it’s still $40 because of distribution bottlenecks. The data’s solid, but the lived experience isn’t always reflected.

Also, the 50-70% patient pass-through rate is terrifying. If a drug drops from $1,200 to $200, why am I still paying $70? PBMs are the hidden middlemen who turn savings into profit. We need transparency laws, not just better stats.

And can we talk about how insulin glargine’s generic is still $100 a vial? That’s not savings-that’s exploitation dressed up as competition.

Julie Chavassieux

Wow.

Candy Cotton

It is an undeniable fact that the United States leads the world in pharmaceutical innovation and regulatory rigor. The FDA’s methodology is not only scientifically sound but also fiscally responsible. To compare it with the Association for Accessible Medicines’ inflated aggregate figures is to confuse causation with correlation. The American healthcare system, while imperfect, remains the gold standard. Any suggestion that generic pricing is manipulated by corporate entities is not only unfounded but also dangerously anti-American.

Furthermore, the notion that pharmacy benefit managers are somehow ‘hoarding’ savings is a baseless smear propagated by those who misunderstand market dynamics. The free market, when unimpeded by political interference, delivers the most efficient outcomes. Period.

Sam Black

Reading this felt like watching a river carve a canyon-slow, relentless, invisible until you step back. The FDA’s yearly numbers? Those are the ripples. The AAM’s $445 billion? That’s the canyon.

What’s wild is how we normalize this. We don’t celebrate the guy who fills your diabetes script for $6.97. We don’t tweet about the cancer drug that dropped from $10K to $2K. But that’s the quiet revolution. It’s not flashy. It doesn’t have a TED Talk. But it’s keeping people alive.

And the biosimilars? They’re the next chapter. We’re just starting to scratch the surface. I hope we don’t let patent thickets and legal loopholes bury this momentum. We’ve got the science. Now we need the will.

Cara Hritz

ok so i read this whole thing and like the FDA thing is cool but like why is the AAM number so much bigger?? i think they just adding up the same savings over and over?? like if a drug was approved in 2020 and still used in 2023, why count it again?? that seems like double counting?? or am i dumb??

Jamison Kissh

There’s a philosophical tension here that mirrors the tension between justice and efficiency. The FDA measures the moment of disruption-the birth of competition. The AAM measures the ongoing legacy of that disruption. One is the spark; the other is the fire.

But what does it mean that the patient rarely sees the full benefit? If savings are captured by intermediaries, is this truly a win for the public? Or is it just a transfer of wealth from pharmaceutical corporations to corporate middlemen?

Generics should be a public good, not a profit engine for third parties. The real question isn’t how much we save-it’s who gets to keep it.

Art Van Gelder

Okay, let me just say this: the fact that we’re even having this conversation means we’re living in a world where a $10,000-a-month cancer drug can be turned into a $200 one-and people still get billed $70 because some guy in a suit in Chicago gets a kickback.

And yet, we’re still the only country on Earth where you need a loan to buy insulin. The irony is so thick you could spread it on toast.

Meanwhile, in Canada, they just cap prices. In Germany, they negotiate. Here? We let the market ‘work’-which means the market works for the people who own it, not the people who need it.

But hey, at least we’ve got 92% of generics under $20. So if you’re lucky enough to have insurance, or a job with decent benefits, or a family that can help you pay out of pocket… you’re golden. If not? Well, congrats-you’re part of the 30% who can’t afford the $6.97 copay because your deductible is $8,000.

So yeah. Savings? Yes. Justice? Not even close.

And Ozempic generics? They’re coming. And when they do, we’re gonna see the same script: $1,000 list price → $150 generic → $90 copay → PBM pockets $100. Again. Always again.

Herman Rousseau

This is one of those posts that makes you feel hopeful and furious at the same time 😔

On one hand: $445 BILLION saved? That’s insane. That’s a whole country’s worth of care covered. Hats off to the scientists, pharmacists, and regulators who made this possible.

On the other: why do patients still feel the pain? Why are PBMs getting rich off our prescriptions? We need to fix the system, not just celebrate the numbers.

Let’s push for legislation that forces transparency-no more black boxes between the drug price and the patient’s wallet. We’ve got the data. Now let’s use it to make things fair.

And hey-if you’re reading this and you’re on a generic med that saves you $100 a month? You’re winning. Keep fighting for the system to catch up with you 💪❤️

Vikrant Sura

So basically, the FDA’s number is useless because it’s too small, and the AAM’s number is meaningless because it’s just a cumulative sum. Both are just numbers dressed up as policy. Real savings? You’re still paying $50 for a $20 drug. The whole system is a scam.

Also, why are we even talking about this? It’s not like anything will change.

Jeremy Hendriks

You know what’s funny? We treat generic drugs like they’re charity. Like they’re some noble sacrifice made by the state for the poor. But they’re not. They’re capitalism at its most ruthless and beautiful: competition kills monopoly, and monopoly kills people.

The FDA doesn’t ‘approve’ generics. It dismantles monopolies. The AAM doesn’t ‘count’ savings. It reveals the cost of corporate greed.

And the PBMs? They’re not middlemen. They’re parasites. They’ve turned a public health victory into a private revenue stream.

So yeah-$445 billion saved. But how much of that was stolen? That’s the real question. And no one’s asking it.

Because if we did… we’d have to burn the whole system down.

And I’m not sure we’re ready for that.