AGEP Probability Calculator

Assess Your AGEP Risk

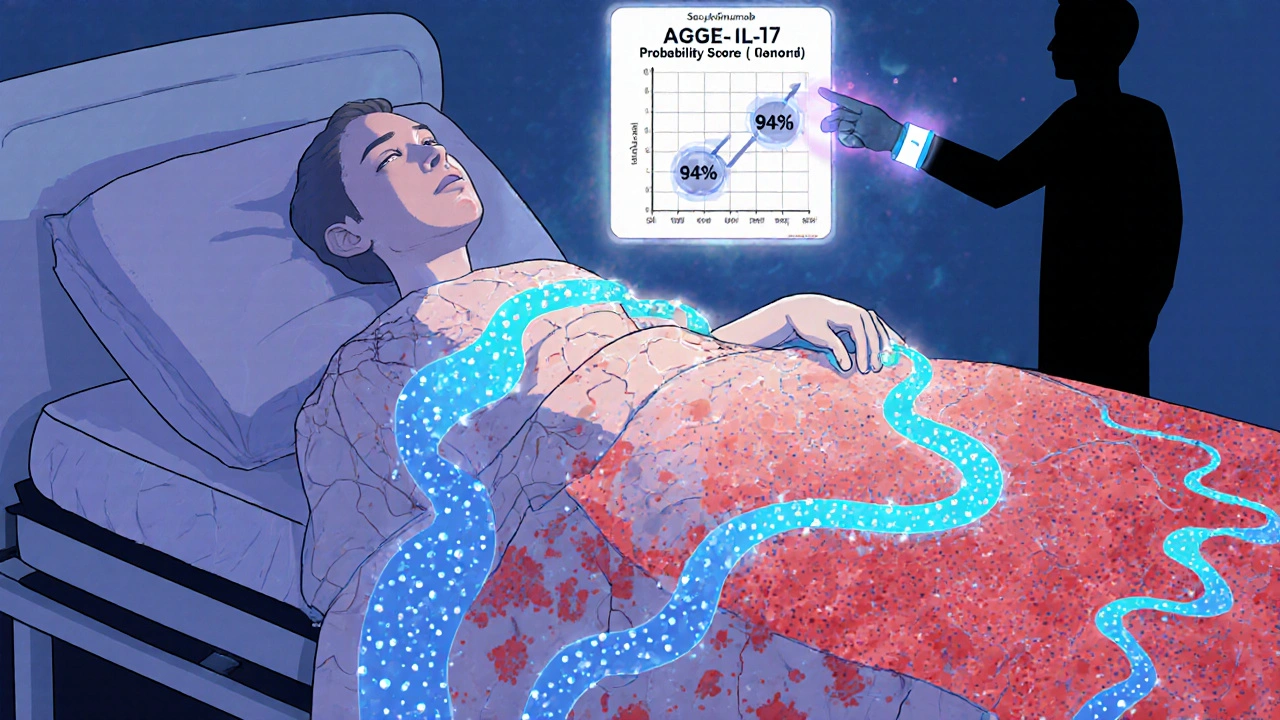

This tool estimates the likelihood of Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis based on clinical features and diagnostic criteria. The AGEP Probability Score (APS) is calculated using 6 key clinical features. A score of 6 or higher indicates 94% certainty of AGEP.

AGEP Probability Score

Your score:

AGEP is one of the most alarming skin reactions you can have after taking a common medication. It doesn’t sneak up on you - it hits fast. Within 1 to 5 days of starting a new drug, your skin erupts in hundreds of tiny, pus-filled bumps. No itching at first, but soon, your body feels hot, your skin burns, and you wonder what’s happening. This isn’t acne. It’s not a fungal infection. It’s Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis - or AGEP - a rare but serious drug reaction that can land you in the hospital if not recognized quickly.

What AGEP Actually Looks Like

Imagine your skin turning bright red, then covered in pinhead-sized white or yellow pustules. They don’t form around hair follicles - they pop up randomly across your chest, armpits, neck, and face. Within 24 to 48 hours, they spread everywhere. You might have a fever over 38.5°C. Your lips might feel dry. Your tongue might sting. You don’t feel sick in the way you do with the flu - you feel like your skin is on fire.

Unlike psoriasis, AGEP doesn’t show thick, scaly plaques. It doesn’t target your palms or soles the way psoriasis sometimes does. The pustules are sterile - no bacteria inside. That’s why antibiotics won’t help. And unlike hives, the bumps aren’t itchy at first. The real clue? It all started after you took a new pill - maybe amoxicillin, clarithromycin, or even a blood pressure medication you’ve been on for months.

What Causes AGEP?

Nearly 90% of AGEP cases are triggered by drugs. Antibiotics are the #1 culprit. In fact, over half of all cases come from beta-lactams like amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate. Macrolides like erythromycin are next. But it’s not just antibiotics. Antifungals, calcium channel blockers, and even anticonvulsants can set it off. And here’s the twist: sometimes the drug was taken weeks earlier. Amoxicillin-clavulanate, for example, can trigger AGEP up to 14 days after you stopped taking it.

AGEP isn’t an allergy in the classic sense. You don’t get hives or swelling. It’s more like your immune system misfires - neutrophils flood your skin, forming pustules. That’s why lab tests show high white blood cell counts, especially neutrophils. Your CRP level spikes too. It’s an inflammatory storm, not an allergic reaction.

How Is AGEP Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t diagnose AGEP by looking at your skin alone. Too many rashes look similar. Misdiagnosis happens in 35-40% of cases, especially outside dermatology clinics. The key is the timeline: rash appears 1-5 days after starting a new drug. The pattern: pustules on red skin, no blisters, no mucous membrane damage. And the lab: neutrophilia, elevated CRP.

A skin biopsy confirms it. Under the microscope, you’ll see pustules just below the skin’s top layer, filled with neutrophils. There’s swelling in the upper dermis. No signs of infection. No fungi or bacteria. If you’ve had psoriasis before, this isn’t a flare. Psoriasis pustules are deeper, last longer, and come with scaling. AGEP clears fast - if you stop the drug.

There’s now a tool called the AGEP Probability Score (APS). Developed by the EuroSCAR group, it uses 6 clinical features - like fever, pustule count, and timing - to give you a score. A high score means 94% certainty it’s AGEP. It’s not perfect, but it’s helping doctors stop guessing.

Treatment: Stop the Drug - Then What?

The single most important step? Stop the medication. Immediately. That’s it. In over 90% of cases, stopping the drug is all you need. The rash starts fading in 2-3 days. Full recovery? Usually within 10-14 days. No scars. No long-term damage.

But here’s where things get messy. Some doctors give steroids. Others say no. Why? Because AGEP heals on its own. Giving prednisone might speed things up by a few days, but it also brings side effects - weight gain, blood sugar spikes, mood swings. A 2023 review found patients on oral steroids stayed in the hospital 3.2 days less on average. But dermatologists at Baylor College of Medicine, who’ve seen 15 cases over three years, say: “Don’t use them unless absolutely necessary.”

So what’s the right call? If you have a mild rash, no fever, and less than 10% of your skin affected - supportive care is enough. Cool compresses, moisturizers, antihistamines for itch, fluids. If you’re running a high fever, have over 20% skin involvement, or feel dizzy and weak - then systemic steroids might be worth considering. Some experts use them in those cases and see resolution in 7 days instead of 14.

There’s a new option: biologics. Secukinumab, a drug used for psoriasis, has been used successfully in AGEP cases that didn’t respond to anything else. One patient in a 2021 case report cleared up in 72 hours after a single shot. It blocks IL-17, a key inflammatory signal in AGEP. This isn’t standard yet - but for patients who can’t take steroids (like those with diabetes or infections), it’s a game-changer.

What Happens After the Rash Clears?

After the pustules go away, your skin peels. That’s normal. It can last a week. This is when people make mistakes. They stop using moisturizer. They go in the sun. They get sunburned. That’s a bad idea. Your skin is vulnerable. Studies show patients given written instructions on sun protection and emollient use had 78% compliance. Those who just got verbal advice? Only 42% followed through.

You’ll need to avoid the drug that caused AGEP - forever. Cross-reactivity is common. If amoxicillin-clavulanate triggered it, you can’t take other penicillins. Your doctor should document this in your chart. You might even want a medical alert bracelet. The European Medicines Agency now requires drug labels to list AGEP as a possible side effect for high-risk medications. That’s new. And it’s saving lives.

Who’s at Risk?

AGEP can happen to anyone - men, women, young, old. But some groups are more vulnerable. People with existing psoriasis have a higher chance. So do those with chronic kidney disease. And there’s emerging genetic data: HLA-B*59:01 is a marker linked to AGEP in Asian populations. People with this gene have nearly 9 times higher risk when taking certain drugs. That’s not something you can test for routinely - yet. But it’s a clue for why some people react and others don’t.

It’s rare - only 1 to 5 cases per million people each year. But it’s not rare enough to ignore. With over 127 confirmed cases linked to amoxicillin-clavulanate in European databases, it’s clear: this isn’t a fluke. It’s a pattern.

The Bigger Picture

AGEP is part of a growing problem: drug-induced skin reactions. The pharmaceutical industry is now required to monitor for these reactions during clinical trials. Regulators like the FDA and EMA are tightening rules. More drugs are being labeled with AGEP warnings. Research is accelerating - 42 papers on AGEP were published in 2022, up from just 15 in 2018.

Future tools? Genetic screening. Better diagnostic scores. Targeted biologics. The International Registry of Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (RegiSCAR) is tracking over 300 AGEP patients to understand long-term outcomes. Early data suggests no increased risk of cancer or autoimmune disease after recovery. That’s reassuring.

What’s next? A revised diagnostic scoring system, AGEP 2.0, is set to launch in early 2024. And phase II trials for secukinumab and other IL-17 inhibitors are showing 92% effectiveness in early results. This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening now.

What Should You Do If You Suspect AGEP?

Here’s your action plan:

- Stop the new medication immediately - don’t wait for a doctor’s appointment.

- Call your doctor or go to urgent care. Say: “I think I have AGEP.”

- Don’t take any new drugs until you’re cleared.

- Keep your skin cool and moisturized. Avoid sun exposure.

- Drink plenty of water. Rest.

- Get a referral to a dermatologist if possible.

Don’t wait for the rash to get worse. Don’t assume it’s “just a reaction.” AGEP is rare - but it’s dangerous if ignored. The sooner you stop the trigger, the faster you recover.

Is AGEP the same as psoriasis?

No. While both cause pustules, AGEP is triggered by drugs and clears within 10-14 days after stopping the medication. Psoriasis is a chronic autoimmune condition with thick, scaly plaques that come and go over years. AGEP pustules are sterile and appear suddenly; psoriasis pustules are deeper and often recur in the same spots. A skin biopsy can tell them apart.

Can AGEP come back after it clears?

Yes - but only if you take the same drug again. Once you’ve had AGEP, your body remembers the trigger. Re-exposure can cause a more severe reaction, sometimes life-threatening. You must avoid that medication for life. Cross-reactivity with similar drugs (like other penicillins) is common, so always check with your doctor before taking any new antibiotic.

Are steroids always needed for AGEP?

No. In fact, many experts advise against them. AGEP resolves on its own in most cases. Steroids may shorten hospital stays by a few days, but they carry risks like high blood sugar, weight gain, and mood changes. They’re typically only considered if you have extensive skin involvement (over 20% of your body), high fever, or signs of systemic illness. For mild cases, rest, fluids, and moisturizers are enough.

What drugs most commonly cause AGEP?

Antibiotics cause over half of all cases. Amoxicillin-clavulanate is the top offender. Other common triggers include erythromycin, minocycline, and antifungals like fluconazole. Non-antibiotics like calcium channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem) and anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine) are also linked. Always consider any new medication taken in the last 1-14 days as a possible cause.

How long does it take to recover from AGEP?

Most people start improving within 2-3 days after stopping the drug. The rash fades over 7-10 days. Skin peeling may continue for another week. Full recovery usually happens within 10-14 days. Hospital stays average 5-9 days for severe cases. Long-term, there’s no scarring or lasting damage - as long as you avoid the trigger drug.

Is AGEP life-threatening?

It can be, but it’s rare. The mortality rate is 2-4%, much lower than Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (which is 10-30%). Death usually happens when the condition is misdiagnosed or when patients have other serious health problems like kidney failure or sepsis. Early recognition and stopping the drug are the best ways to avoid complications.

Conor McNamara

so i read this and im just thinkin… what if the drugs aint the real problem? what if its the fillers? the preservatives? the damn microplastics in the capsules? i mean, amoxicillin’s been around since the 40s but now suddenly everyone’s breaking out? nah… something changed. they added something. something silent. something in the factory. they dont tell you that part.

Leilani O'Neill

Of course the Irish health system can’t handle this. We don’t even have a national dermatology registry. Meanwhile, Germany has a 12-point diagnostic algorithm and a national AGEP hotline. This isn’t medicine-it’s a lottery. And we’re the ones stuck with the losing ticket.

Riohlo (Or Rio) Marie

Let’s be brutally honest: AGEP isn’t a ‘rare reaction’-it’s a systemic failure of pharmacovigilance. The pharma giants don’t test for it because it’s inconvenient. They know neutrophilic pustulosis is a red flag, but they bury it in footnotes. And then they slap a ‘may cause rash’ disclaimer on the bottle like it’s a warning on a bag of chips. The real tragedy? It’s preventable. But profit prefers ignorance over integrity.

And don’t get me started on the steroid debate. It’s not about ‘side effects’-it’s about who gets to decide what ‘mild’ means. A patient with 15% body involvement isn’t ‘mild’-they’re screaming into a void while their skin peels like a sunburnt apple.

Secukinumab? Brilliant. But only if you’re in a country that can afford it. In the U.S., one dose costs more than my rent. So we’re left with a two-tiered medicine: the rich get biologics, the rest get ‘cool compresses and good vibes.’

And yes, I’ve seen it. My cousin got it after amoxicillin. They discharged her with a pamphlet. Three days later, she was in ICU. The ER doctor said, ‘Probably just a virus.’

steffi walsh

Thank you for writing this. I had AGEP last year after a course of amoxicillin for a sinus infection. I thought it was heat rash at first. Then my face felt like it was on fire. I cried because I didn’t know what was happening. But I stopped the med right away and used aloe vera and cold towels. It took 10 days but I’m fine now. Please, if you’re reading this and you’re scared-you’re not alone. It’s scary, but it’s not forever. 💛

Yash Nair

indians dont get this shit. we’ve been taking antibiotics since the 70s and our skin is tougher than your fancy european skin. this is a first world problem. stop being weak. if you cant handle a little rash, maybe you shouldnt be popping pills like candy.

Bailey Sheppard

This is such a well-written breakdown. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen a few cases-always shocking how fast it comes on. I love how you emphasized stopping the drug immediately. So many patients wait for the ‘doctor’s okay’ and lose precious hours. Also, the secukinumab mention? That’s huge. I’ve got a patient on it now-her rash vanished in 48 hours. Hope this gets more attention.

Girish Pai

From an immunology standpoint, the neutrophilic cascade is the key. IL-17/IL-23 axis dysregulation is the mechanistic backbone-this isn’t just a rash, it’s a cytokine storm localized to the epidermis. The HLA-B*59:01 association in South Asian populations is underreported in Western literature. We need genomic screening protocols integrated into primary care, especially for high-risk cohorts. Also, the 14-day delayed onset with amoxicillin-clavulanate? Classic Type IV hypersensitivity kinetics. We’re not talking allergies-we’re talking T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Time to update the textbooks.

Kristi Joy

Thank you for sharing this. I’ve been a dermatology nurse for 18 years and I still see patients dismissed because ‘it’s just a rash.’ This post could save someone’s life. Please, if you’re reading this and you’re worried-trust your gut. Stop the drug. Call your doctor. And if they brush you off, go to urgent care and say ‘I suspect AGEP.’ You deserve to be heard. You’re not overreacting. You’re being smart.